Nancy and Tony on Pussycat Hill where the triumph and tragedy of Donald Campbell is told above Dumbleyung Lake, now a salty expanse.

Community spirit oozing through the wheat fields, wildflowers and woolly sheep of the great lakes district propelled Donald Campbell to a world water speed record in Western Australia in the dying hours of 1964.

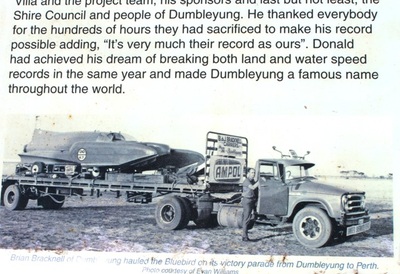

After tootling across Dumbleyung Lake at 442.08 km an hour in Bluebird, the fastest man on land and sea paid tribute to the townsfolk of Dumbleyung. When the Bluebird team had arrived unexpectedly at the biggest lake in Western Australia, men and women from the town sacrificed hundreds of hours to support the effort to set a water speed record.

Without the community swinging behind him, Donald said, he would never have made that victorious spurt when his team was within hours of having to call the whole thing off. “It’s very much their record as ours,” he told the victory dinner.

We arrived at the eastern end of the lakes and wheat belt in the dark after taking the lonely Cascades Road through the back country from Esperance. We had dreamed earlier in the day of a cosy pub where we could park Isabel nearby and enjoy a hearty meal.

We had given up hope but drove into Lake King and presto! The Lake King Tavern turned up trumps and showed us why it was a finalist in the “best regional tavern in WA” awards in 2013.

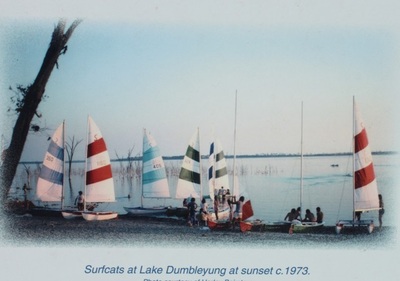

Remnants of an ancient great river that flowed and dramatically ebbed millions of years ago, the lakes used to regularly fill with fresh water after rains and dry up into salt pans in drought. Picnics and horse races have been held in dry times; in the wet sailing races, speed boating are other activities are held on water up to 4.5m deep.

Lake King has a causeway stretching over 10km of lakes that were pretty much salt pans when we drove through. Where water a few centimetres deep remained changes in the wind created tides, sending water scooting from one side of a lake to another.

Land clearing and farming has hastened the salt pan formations. Everyone is pulling together to try to reverse the salination because that’s what they do in these towns: pull together.

Newdegate’s fabulous public loo is evidence of the community spirit and it shone through at Lake Grace. Tourist officer Anna Naisbitt told us how the town rallied in 1923 when postmistress Eileen West decided to campaign for an Australian Inland Mission hospital.

The 15 AIMs built by the Presbyterian Church were the brainchild of Rev. John Flynn, who had a vision to spread a “mantle of safety” to women and children in outback Australia. He had seen too many lonely outback graves. Later Flynn of the Inland was to found the Royal Flying Doctor service.

The Lake Grace AIM was agreed to in 1925, the same year Eileen organised a line of pennies to run from the post office for the appeal. The building was opened in 1926 and the debt paid off by the community. The nursing home was outgrown by 1952 when a new hospital was built next door. It had a number of uses but in 1983 was shabby and empty.

“Demolish it,” said the State Government.

“Bugger that,” said the people of Lake Grace and the community spirit went into action. More than 100 volunteers raised funds, replaced floorboards, guttering and fences, restumped the verandah and saved a cracker tourist attraction that is now on local, state and national heritage registers.

Brisk and friendly Elsie Bishop bustled into the tourist centre. She’s 86, volunteers at the centre every Thursday and is a lively escort on tours around the AIM. She and her husband Bill are retired wheat and sheep farmers.

“The old families around here are the mainstay of Lake Grace,” said Anna. She listed a few. My ears pricked up when she mentioned Slarke.

“That’s an unusual name,” I said slowly. “They didn’t by any chance have twin sisters …?” Yes, said Anna. Kelly and Stacey Slarke from Lake Grace were among the 15 young people who died in the ghastly Childers backpacker hotel fire in 2000.

A sombre touch came to our day as Anna recalled the day the little town was shattered by the news from Queensland.

We pushed on eastwards, past the town’s cemetery where school kids had gathered in January 2006 to be ferried to school by boat. A gruelling drought had been broken by 13 inches of rain in 24 hours. Lake Grace turned into a sea.

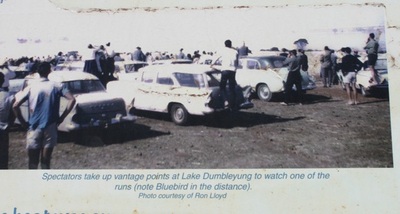

At Dumbleyung Lake we surveyed the salt flats from Pussycat Hill and tried to envisage that marvellous day in 1964 when a blue bubble hurtled across the water, taking Donald Campbell to glory and earning Dumbleyung legendary status.

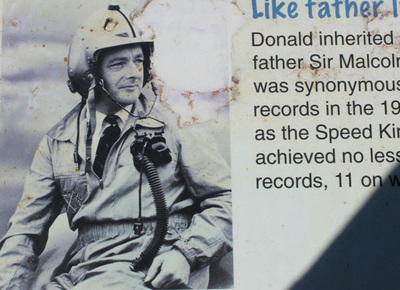

Donald’s dad, Sir Malcolm Campbell, was a speed demon in the 1920 and 1930s. Father and son set 21 world speed records between them, 11 on water and 10 on land.

Donald remains the only person to have broken land and speed records in one year – with a few hours to spare thanks to the good folk of Dumbleyung.

In 1964 he set a new world land speed record at Lake Eyre and set his sights on breaking both land and water speed records in one year. He had a crack at breaking the water speed on Lake Bonney in South Australia but conditions were unsuitable. He was about to give up when he was told about the lake with a strange name in the WA southern wheatbelt.

Donald and the Bluebird team arrived at Dumbleyung on December 12 and the whole town pitched in to help. Next day conditions were ideal but Donald had to abandon a trial run because flocks of ducks arrived too. In hot, frustrating December days that followed, wind stirred up waves to make the attempt impossible.

Donald had all but given up hope when New Year’s Eve dawned. Suddenly, with hours to spare, the wind stopped. Everyone (including people appointed as duck scarer-offers) rushed to their positions. Donald completed two blistering runs and blasted the old record.

Two years later Donald tried to push the ageing Bluebird to a new record at Lake Coniston in England.

The transcript of his last words to his crew:

160kph: “Passing Peel Island, tramping like mad, full house.”

320kmh: “The water’s very bad indeed …. I can’t get over the top.”

480 kmh: “I’m getting a lot of bloody row in here … I can’t see anything.”

550kmh: A new world record.

460kmh: “I’ve got the bows out … I’m going.”

Three seconds from victory, the Bluebird lifted out of the water and killed Donald instantly in a backwards somersault.

On Pussycat Hill at Dumbleyung, December 31, 1984, 20 years after the world record was set, Donald’s daughter Gina unveiled a monument to the king of speed. On that date every year (provided it’s not overcast, I suppose) a shaft of sunlight shines through a hole in the monument at 3.43pm – the exact time the record was broken.

The full stop for our run through the wheat and sheep belt was in the next town of Wagin, where a 9m high, exceptionally well-endowed ram made a couple of emphatic punctuation marks. At 13m in length, the biggest damned ram in the southern hemisphere was fund-raised for and then raised in all its masculine glory by – you’ve guessed it – community spirit.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed