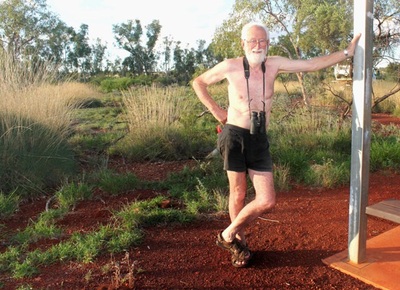

He was easily spotted as a bird-spotter. A pair of shorts, no-nonsense boots and socks, grey-haired and 70ish with a serious pair of binoculars around his neck, Graeme George had that alert manner and focus that distinguishes avid bird watchers.

He was more than that. A permaculture ecologist from Victoria, he studies habitats as well as noting species of birds. He likes to figure out why certain birds are found in some areas and not others; what food, fauna and climate they need to survive. He also has some pretty strong views on how the human species is going to survive in its habitat.

We found Graeme prowling around the homestead campsite in the Pilbara’s Millstream Chichester national park. He was in good spirits, buoyed by a refreshing plunge in the nearby Deep Reach pool and well pleased with his first sighting of star finches.

Tony and I had had a grumpy introduction to the park, being given the runaround because the first two campsites we wanted were closed without much notice but, as can happen, it didn’t work out too badly.

We had more time to explore the cool, airy Millstream homestead (above) and its surrounds. The pastoral lease was taken up about 1866 for the station along spring-fed pools rising from the plains and forming a tributary for the Fortescue River. Explorer F. T. Gregory noted in 1861 that the stream was “running strong enough to supply a large mill”, giving the station its name.

At its peak Millstream covered a million acres and carried 55,000 sheep. It once held the Australian record for the highest price paid for a fleece.

The second homestead was built in 1914 with wide verandahs and altered only minimally when turned into a visitor centre in 1990. A detached corrugated iron kitchen with a high curved roof still contains an impressive wood stove with ovens.

A rambling walk goes past what was once an ant bed tennis court, beside what was once an expansive vegetable garden (rice and cotton were among plants grown but apparently no one knew how to harvest them) and wanders through a grove of hundreds of date palms to the water-lilied lagoon. Scattered along the paths were plaques peeking into the past with slightly haphazard first person quotes.

Millstream is a rare haven in the ancient, parched landscape of the red-rocked Pilbara. Rare too was the camp kitchen which almost made up for our disappointment at not being able to have a campfire when we became reluctant overnighters.

Possibly one of the finest national parks kitchens created to date, Millstream’s offering to campers has been built on the same design as the detached kitchen at the homestead, with a curved corrugated iron roof, verandah and clean tiles.

A long tiled central bench separated the gas stove with barbecue at one end and the washing up area with Graeme at the other.

He had hit the road in his trusty ute for a two-month break from busy rounds of meetings back home in Victoria. Semi-retired and still lecturing, he explained that permaculture had evolved because the heady growth of everything in the world was believed to be leading to a global collapse.

Transport, communication, food production and energy supplies could fail dramatically so those who had the means to be self-sufficient would survive. Permaculture had broadened beyond its initial grow-vegies-spin-wool base sustainability to encompass much more of mankind’s activity.

I had to ask the question. “What do you consider to be the greatest threat to mankind and the planet.” The answer came without hesitation. I nearly hugged him. Here was an educated, environmentally aware Victorian with a clear focus on the root cause of our problems but one that never seems to get air in the subjective, emotional and sneakily financially self-serving debates about carbon, climate change and rising sea levels.

“Overpopulation – and over-consumption,” said Graeme firmly. Unless we fix those two things civilisation as we know it will collapse. Yes! Here’s a bare-chested Victorian environmentalist singing my song.

We agreed that education of women was critical to saving the planet. Not higher education in developed countries so well-heeled females could spend, spend and spend but basic education for women in developing countries that would lead to them controlling their fertility. We also need corporate success to be measured in regenerational growth, not exponential growth.

I slept soundly. Maybe it was the wine. As we watched Graeme stalking birds the next morning I wondered if I should start growing grapes. Then I remembered my mother’s vintner foray with a potent poison that was supposed to be nectarine wine.

We drove off to admire the dramatic landscape in the park of almost 240,000 hectares, heading for the Python Pool that had been our initial destination. It was not at its most spectacular, a little stagnant but with prettily green algae on the surface around the edges. A sign said not to swim if the algae were in bloom.

A procession of work-like vehicles arrived and disgorged occupants who plunged into the pool. Apparently after driving a few hundred kilometres to get there from anywhere else you are not going to be deterred by a fluffy bit of algae bloom.

We slipped the swim and headed for the coast. I wondered what effect the algae had on Pilbara swimmers and whether gentle permaculturalists had extended their preparations for doomsday to include defence strategies.

How would they protect their pockets of self-sufficiency from invasions from hungry hordes clutching high heels, pushing Ferraris that had run out of fuel and fanning themselves with dead tablets? You would have to have a hidden cellar for the wine.

He was more than that. A permaculture ecologist from Victoria, he studies habitats as well as noting species of birds. He likes to figure out why certain birds are found in some areas and not others; what food, fauna and climate they need to survive. He also has some pretty strong views on how the human species is going to survive in its habitat.

We found Graeme prowling around the homestead campsite in the Pilbara’s Millstream Chichester national park. He was in good spirits, buoyed by a refreshing plunge in the nearby Deep Reach pool and well pleased with his first sighting of star finches.

Tony and I had had a grumpy introduction to the park, being given the runaround because the first two campsites we wanted were closed without much notice but, as can happen, it didn’t work out too badly.

We had more time to explore the cool, airy Millstream homestead (above) and its surrounds. The pastoral lease was taken up about 1866 for the station along spring-fed pools rising from the plains and forming a tributary for the Fortescue River. Explorer F. T. Gregory noted in 1861 that the stream was “running strong enough to supply a large mill”, giving the station its name.

At its peak Millstream covered a million acres and carried 55,000 sheep. It once held the Australian record for the highest price paid for a fleece.

The second homestead was built in 1914 with wide verandahs and altered only minimally when turned into a visitor centre in 1990. A detached corrugated iron kitchen with a high curved roof still contains an impressive wood stove with ovens.

A rambling walk goes past what was once an ant bed tennis court, beside what was once an expansive vegetable garden (rice and cotton were among plants grown but apparently no one knew how to harvest them) and wanders through a grove of hundreds of date palms to the water-lilied lagoon. Scattered along the paths were plaques peeking into the past with slightly haphazard first person quotes.

Millstream is a rare haven in the ancient, parched landscape of the red-rocked Pilbara. Rare too was the camp kitchen which almost made up for our disappointment at not being able to have a campfire when we became reluctant overnighters.

Possibly one of the finest national parks kitchens created to date, Millstream’s offering to campers has been built on the same design as the detached kitchen at the homestead, with a curved corrugated iron roof, verandah and clean tiles.

A long tiled central bench separated the gas stove with barbecue at one end and the washing up area with Graeme at the other.

He had hit the road in his trusty ute for a two-month break from busy rounds of meetings back home in Victoria. Semi-retired and still lecturing, he explained that permaculture had evolved because the heady growth of everything in the world was believed to be leading to a global collapse.

Transport, communication, food production and energy supplies could fail dramatically so those who had the means to be self-sufficient would survive. Permaculture had broadened beyond its initial grow-vegies-spin-wool base sustainability to encompass much more of mankind’s activity.

I had to ask the question. “What do you consider to be the greatest threat to mankind and the planet.” The answer came without hesitation. I nearly hugged him. Here was an educated, environmentally aware Victorian with a clear focus on the root cause of our problems but one that never seems to get air in the subjective, emotional and sneakily financially self-serving debates about carbon, climate change and rising sea levels.

“Overpopulation – and over-consumption,” said Graeme firmly. Unless we fix those two things civilisation as we know it will collapse. Yes! Here’s a bare-chested Victorian environmentalist singing my song.

We agreed that education of women was critical to saving the planet. Not higher education in developed countries so well-heeled females could spend, spend and spend but basic education for women in developing countries that would lead to them controlling their fertility. We also need corporate success to be measured in regenerational growth, not exponential growth.

I slept soundly. Maybe it was the wine. As we watched Graeme stalking birds the next morning I wondered if I should start growing grapes. Then I remembered my mother’s vintner foray with a potent poison that was supposed to be nectarine wine.

We drove off to admire the dramatic landscape in the park of almost 240,000 hectares, heading for the Python Pool that had been our initial destination. It was not at its most spectacular, a little stagnant but with prettily green algae on the surface around the edges. A sign said not to swim if the algae were in bloom.

A procession of work-like vehicles arrived and disgorged occupants who plunged into the pool. Apparently after driving a few hundred kilometres to get there from anywhere else you are not going to be deterred by a fluffy bit of algae bloom.

We slipped the swim and headed for the coast. I wondered what effect the algae had on Pilbara swimmers and whether gentle permaculturalists had extended their preparations for doomsday to include defence strategies.

How would they protect their pockets of self-sufficiency from invasions from hungry hordes clutching high heels, pushing Ferraris that had run out of fuel and fanning themselves with dead tablets? You would have to have a hidden cellar for the wine.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed