Ruth Duncan, a striking blonde in her twenties, was swept into a saga of a charismatic Kimberley man, a mysterious rare stone and a trail of dreams that is leading to a 7m high waterfall tumbling into a unique pool.

Add a zebra rock mine and a gallery crammed with sculpted treasures crafted from nature’s artistic efforts 1.2 billion years ago. Think rock ’n’ roll beside the waterfall: it all swirls around the extraordinary Kim Walker and is coalescing into mecca for Australian travellers.

We had seen zebra rock on sale at a few touristy shops on visits to the north-west but were unprepared for what unfolded when we stumbled upon the Zebra Rock Mine with its gallery and campground.

Following the signs we turned Isabel south on to the Duncan Road from the Victoria Highway, 11km east of the WA border. Five kilometres down the road you turn off towards the western side of Lake Argyle. Another 5 km down is an astonishing enterprise opened to the public two years ago.

A path led through a couple of dozen caravans and motor homes to the gallery and gift shop where vivacious Ruth captivated us with stories of the mystery properties of zebra rock, the Argyle legend and the news that the mine she and Kim own will within a few years be the world’s only commercial producer of the striking stone, evenly striped and marbled with patterns of iron.

Zebra rock is found only in the Lake Argyle area. One island where it was mined was flooded by the Ord River dam that created the giant lake and the irrigation scheme to nourish an agricultural district centred on Kununurra. In 2018 the other will disappear when the dam is raised another 6m.

Ruth explained that the rhythmic patterns of iron in the rock had long fascinated and baffled scientists.

“There’s nothing like it anywhere in the world. Geologists have been unable to explain the natural flowing patterns. Monash University has come up with the latest explanation that the rock was in a fluid state during its formation.”

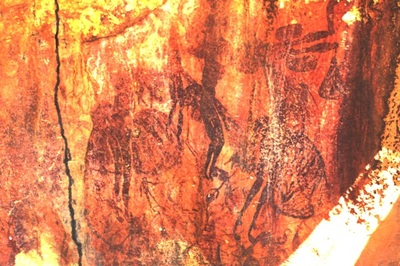

That could have formed the stripes and bubbles between the layers of sediment, although unusual factors continue to puzzle the experts. Manganese needs to be exposed to at least 1000 degrees of heat to form the stylised iron patterns: how did that happen? Why is zebra rock not found anywhere else in the world? How did the rock go through the process of cracking in straight lines and then welding itself together with opalised seams?

“Everyone thinks it looks broken but it’s solid,” said Ruth. “It’s beautiful stone and the patterns are amazing.”

Zebra rock has a fascination that can become an obsession. As a young boy growing up on Argyle station in the 1950s, Kim Walker played with it, wondered about it and was destined to be haunted by it for the rest of his life.

His father was head stockman on Argyle Downs a few years after the break-up of the cattle empire built by the pioneering Durack family, immortalised in the book Kings in Grass Castles. Restless Kim (short for Kimberley, naturally) used the skills he absorbed as a child to work in Western Australia and the Territory as a bullcatcher. For 20 years he caught wild bulls, worked as a contracrtor and put in stints as a miner.

Rocks and minerals fascinated him as he roamed, collecting specimens such as the 800m wide block of quartz crystals sitting in the new gallery. Above it is a compelling series of photographs taken by the Sydney Morning Herald in 1985 showing Kim, with long blonde hair and bare chest, wrestling wild bulls into captivity beside the open 4WD.

“You won’t see photos like that any more,” said Ruth.

He never settled. “No woman would have put up with me when I was young,” he says when we met him later. “And there’s not too many women who would want to spend 35 to 40 years in a swag.”

For 15 years he returned to the Lake Argyle area in the wet, searching for outcrops of the alluring zebra rock. The wet is down-time in the north-west and moisture on the rocks made the patterns easier to spot. He narrowed down his search and started thinking about mining rights and land ownership.

“Then he took another 10 years to find me,” smiled Ruth. “He sailed around the seas on a 70ft yacht and then found me back at the back of Kununurra, working in 48 degree heat.”

He asked the sweating Victorian hydrologist for her phone number and a powerful mutual attraction conquered the age difference.

“Kim is unique, just as interesting as the landscape he is most at home in,” said Ruth. “The initial interest was sparked by the highly polite and shy manner in the way he asked for my phone number.

“As it turned out, as a hydrologist I had the right set of skills.”

Five years ago they moved to the mine site. “Nothing was here except thick bush and scrub,” said Ruth. They mined, cleared the land and built basic living quarters (Kimberley open plan – that means a roof and a dirt floor), a workshop, a gallery and a kiosk.

Kim sold his luxury yacht to help finance the mine. Ruth sold her 100-year-old home on the Goulburn River in Victoria, complete with hand-made bricks and historic kiln on-site.

Some of the mining for delicate jewellery stone is done with pick and shovel; the big stuff (some table settings are 1.2 tonnes) is done with an excavator.

“Kim had to sell his Harley to buy the excavator,” said Ruth. “That really hurt. He used to have 20 bull-catchers but they were all sold except for one sole survivor which he treasures.”

Ruth learnt to make the jewellery as her Kimberley man of vision and talent turned to another skill: sculpture. Carving, chipping and sanding to bring out the best of the stone he loves, Kim created unique stone bowls, tables and rare treasures.

“Sometimes you can work for months on a piece and it is in the gallery only a few days before it’s gone,” he said.

They started wholesaling to tourist outlets but were annoyed by the high retail mark-ups. They decided to retail their own work. Two years ago they opened the camping ground and gallery, offering mine tours and five safari tours, including fishing on Lake Argyle.

Baby Opal Kimberley Anne, now a 20-month charmer, added to new element to the venture.

Ruth looks around the gallery that symbolises her new life, smiles and lifts shoulders and eyebrows. “I am still wondering what happened.”

She can’t imagine returning to city life. “I very much enjoy the wide open spaces. We are both looking forward, not back.”

She is also bemused to find herself on the edge of the Territory living on a road named after her grandfather’s surveyor cousin Ron Duncan, whose photograph hangs prominently in the gallery.

When the business opened, thefts of large and small zebra rock pieces, worth anything from fifty to several thousand dollars, were a problem, forcing Kim and Ruth to close the mine tours and have a bag check-on for anyone entering the gallery.

Now they are starting to forge ahead with plans for next year. Already word is spreading from campers who love the Zebra Rock Mine experience where they can fossick in the creek or gossip around the open restaurant area beside the gallery.

Ruth’s superb fresh-based scones, with jam and fresh cream, are on sale at $3 a pop “and the price will not go up as long as I am here”. She was taught to make them by Aileen Hackett, a Kimberley matriarch who founded and owned the Zebra Rock Gallery in Kununurra for 40 years. Already famous are their fish and chips, using silver cobbler from the lake.

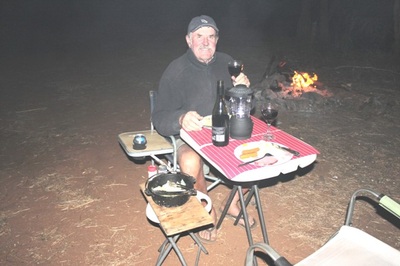

Ten dollars a person a night (Kim vows it will not go any higher as long as he is alive) give you basic campground facilities and free tea and coffee. A campfire is lit at night.

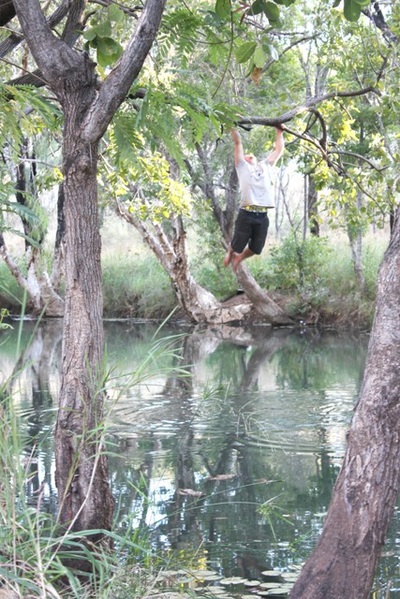

A dam has been built and next year will be raised 5m, stretching 1.5km and creating more wetlands. Here’s where an artistic hydrologist with superb people skills comes in handy. Kim has planned a 50ft waterfall to tumble into a swimming pool that will be built this summer.

Beside it will be a dance floor. Rock ’n’ roll music will play at night. A new camping area will be opened up further away for those who want to escape from Buddy Holly and the Beatles.

“Everyone thinks old people are old and buggered but they’re not,” said Kim emphatically. “They still want to get up and dance. We’ll do everything ourselves to keep the costs down. We want to cater for older people and for young families with kids.”

His energy and vision is infectious. They might re-open the mine next year under tighter security. He wants to have a restaurant boat taking up to 40 people on the lake with seafood dinners. Palm trees will create an oasis effect.

And then he will build a proper house. “More than 35 years in a swag and I’m still sleeping in one on a dirt floor.” He grins and shakes his head. “At least it’s a double one now.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed