Fuel, food, water, but sorry, no smokes: Part of the family that spent the night camped beside their Patrol, out of fuel and food about 80km from home.

Bill Olive has a gammy leg, crooked and strapped up, but he gives you the impression he is the sort of guy you wouldn’t want to mess with too much.

In 1985 he slid a donga off the back of a truck and pushed it into place with a D4 on the Great Top Road front of his property near the Northern Territory border.

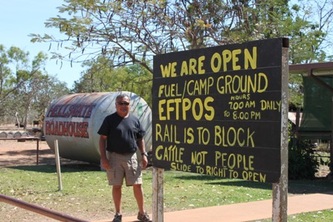

“That was two days before they brought in GST. Great timing wasn’t it?” he said wryly from behind the counter at Hell’s Gate Roadhouse, 90km west of Doomadgee Aboriginal community.

From the donga he stepped out his vision for a service station and built the framework. Hamburgers were sold from the back kitchen and fuel from 44-gallon drums. He built amenities for a caravan park, saved up until he could afford bowsers and took out a liquor licence.

That built up a solid trade, turning over close to $500,000 a year before the licensing commission clamped down. Tough restrictions limiting alcohol destined for Doomadgee went on the roadhouse three years before being implemented at hotels.

“They knocked the stuffing out of the business,” said Bill. In disgust he more or less shut down the roadhouse to a low-key operation and worked the cattle property, returning to the enterprise at night.

“The caravan park always operated and we were open for emergencies. Anyone wanting emergency fuel had to wait until we came home at night.”

Now he is back doing a busy trade in the dry season with increasing numbers of outback wanderers. Business had been aided by closing of Tirranna roadhouse between Doomadgee and Burketown.

We had had an intriguing encounter with a Doomadgee family that morning as we drove north from Kingfisher Camp to the Great Top Road, better known now by its more touristy name of The Savannah Way.

A bloke of about 40 waved us down about 15km from Kingfisher. His Patrol had run out of fuel and his family, an assortment of two mothers and seven cousins, had spent the night camped beside the road.

Phil pulled out his container with 20 litres of spare fuel. As he and Tony poured fuel into the Nissan, Barb and I wandered over to see the grandmother and young mother on a blanket in the shade of a bush.

They were OK, they said, but asked for water. Did the children have anything to eat? No, they said. I found a bottle of water and some biscuits. Barb found some assorted cans of food. No, we said, we didn’t have any smokes.

With a flurry of thanks and broad grins, the children devoured the food as the younger mother said they had gone on a weekend fishing trip at the Fish River outstation. They had stayed an extra day catching bream and catfish.

Tony took note of the fuel bleeder as old mate restarted the Nissan. It was worn. Running out of fuel was not uncommon, apparently. Neither was travelling in the outback with only a little water and no food. Neither did old mate have any money to pay for fuel.

The women hopped in the cab, the kids swung on to the back and they were happily on their way to Doomadgee, about 80km away.

With a chorus of farewells and thank yous, they turned east as we turned west at the highway, where the ruins of Corinda are found. Police stationed there in the 1890s regularly escorted settlers as far west as the rocky escarpments of the Constance Range, which runs north from Bootjamulla (Lawn Hill).

Police officers refused to go with travellers beyond the hills because of the fierceness of Aboriginals in that area, giving rise to its name of Hell’s Gate.

They’re a tough breed out here, the native animals, the people who choose to live here and the feral animals that survive and thrive. We camped at the Robinson River on the dirt road to Borroloola and listened to the latter.

Our sleep was punctuated by the bellowing of lonely rival bulls, the challenging whinnying of a couple of stallions and the squawling of a herd of donkeys.

Bill Olive has a gammy leg, crooked and strapped up, but he gives you the impression he is the sort of guy you wouldn’t want to mess with too much.

In 1985 he slid a donga off the back of a truck and pushed it into place with a D4 on the Great Top Road front of his property near the Northern Territory border.

“That was two days before they brought in GST. Great timing wasn’t it?” he said wryly from behind the counter at Hell’s Gate Roadhouse, 90km west of Doomadgee Aboriginal community.

From the donga he stepped out his vision for a service station and built the framework. Hamburgers were sold from the back kitchen and fuel from 44-gallon drums. He built amenities for a caravan park, saved up until he could afford bowsers and took out a liquor licence.

That built up a solid trade, turning over close to $500,000 a year before the licensing commission clamped down. Tough restrictions limiting alcohol destined for Doomadgee went on the roadhouse three years before being implemented at hotels.

“They knocked the stuffing out of the business,” said Bill. In disgust he more or less shut down the roadhouse to a low-key operation and worked the cattle property, returning to the enterprise at night.

“The caravan park always operated and we were open for emergencies. Anyone wanting emergency fuel had to wait until we came home at night.”

Now he is back doing a busy trade in the dry season with increasing numbers of outback wanderers. Business had been aided by closing of Tirranna roadhouse between Doomadgee and Burketown.

We had had an intriguing encounter with a Doomadgee family that morning as we drove north from Kingfisher Camp to the Great Top Road, better known now by its more touristy name of The Savannah Way.

A bloke of about 40 waved us down about 15km from Kingfisher. His Patrol had run out of fuel and his family, an assortment of two mothers and seven cousins, had spent the night camped beside the road.

Phil pulled out his container with 20 litres of spare fuel. As he and Tony poured fuel into the Nissan, Barb and I wandered over to see the grandmother and young mother on a blanket in the shade of a bush.

They were OK, they said, but asked for water. Did the children have anything to eat? No, they said. I found a bottle of water and some biscuits. Barb found some assorted cans of food. No, we said, we didn’t have any smokes.

With a flurry of thanks and broad grins, the children devoured the food as the younger mother said they had gone on a weekend fishing trip at the Fish River outstation. They had stayed an extra day catching bream and catfish.

Tony took note of the fuel bleeder as old mate restarted the Nissan. It was worn. Running out of fuel was not uncommon, apparently. Neither was travelling in the outback with only a little water and no food. Neither did old mate have any money to pay for fuel.

The women hopped in the cab, the kids swung on to the back and they were happily on their way to Doomadgee, about 80km away.

With a chorus of farewells and thank yous, they turned east as we turned west at the highway, where the ruins of Corinda are found. Police stationed there in the 1890s regularly escorted settlers as far west as the rocky escarpments of the Constance Range, which runs north from Bootjamulla (Lawn Hill).

Police officers refused to go with travellers beyond the hills because of the fierceness of Aboriginals in that area, giving rise to its name of Hell’s Gate.

They’re a tough breed out here, the native animals, the people who choose to live here and the feral animals that survive and thrive. We camped at the Robinson River on the dirt road to Borroloola and listened to the latter.

Our sleep was punctuated by the bellowing of lonely rival bulls, the challenging whinnying of a couple of stallions and the squawling of a herd of donkeys.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed