Cadoux was slumbering amid golden fields shimmering in the heat when we called. Admittedly most northern wheat belt towns of Western Australia slip into hibernate mode in the week between Christmas and New Year but Cadoux felt like it had stopped. So quiet.

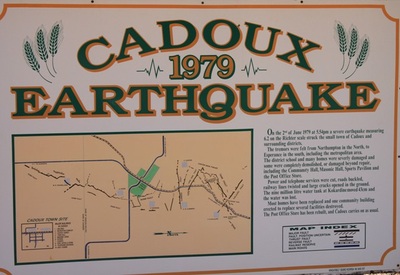

Hard to imagine was the scene at 5.54pm on June 2, 1979, when the roads we saw shimmering in the midsummer heat danced to a different jig in the evening winter gloom.

Cadoux seems such an unlikely place for a powerful earthquake, but it was hit by a convulsion measuring 6.2 on the Richter scale. It opened 15km of great cracks in the ground, buckled roads, twisted railway lines, and cut power and telephone lines.

Left wrecked were the community hall, the Masonic hall, sports pavilion and the Post Office Store. WA’s second biggest earthquake (the biggest was a 7.3 at Meeberrie Station in 1941) moved the hamlet’s nine million litre water tank 43cm: unsurprisingly all the water leaked out.

Twenty-one of the 25 masonry buildings in Cadoux were damaged; only four of the 29 non-masonry were damaged. Falling masonry broke a child’s arm – the only recorded injury.

Most tall buildings swayed 200km away in Perth but little damage was recorded there, apart from the mercury leaking out of the Rottnest Island lighthouse.

After the ground stopped shaking damage to the school and houses was repaired, a new Post Office store built and an entirely sensible solution implemented for the lost recreation and social structures. All were gathered into the grand Cadoux Recreation Centre with social, sporting and cultural amenities – an astonishing air-conditioned complex for a tiny town of four houses, one occupied by the school principal.

Tennis, squash and basketball courts at the centre are used by the school and families living in the surrounding agricultural district.

For only $7 (pick up the key at the Post Office Store up the road), travellers can pull up motor homes or caravans for the night and use the kitchen and showers.

I also found a full bottle of Carlton Dry beer at the campground but alas, unlike the full can of Tooheys New I picked up on the Dundee Beach near Darwin, the free beer was a little spoiled by the sun. I shall continue to keep my eyes open on the free beer treasure hunt around Australia.

How utterly hospitable is Cadoux, little pinprick on the map selected for a wheat railway siding in 1929.

It was originally called Cado after the man who owned the farm where the bulk storage depot was built. A smart clerk did some checking and found the man’s name was actually Donald Cadoux, a French Canadian.

Pronounced a la francaise, Cadoux is phonetically Cado, which explained the anomaly when the name was written down. The council spelling was changed and the locals tweaked the sound to suit their sturdy English heritage. Instead of being pronounced Cado, Cadoux is now pronounced Cadoo.

Poor Donald never had to endure his name being tortured. He was killed at Gallipoli.

Apart from its fine recreation centre, peaceful stopover and hospitality, Cadoux has its Post Office Store, a rural supplies store, service station and its primary school for 25 pupils drawn from the surrounding area.

And despite the dried golden landscape, the Wongan-Ballidu shire where the town nestles has never been declared drought-stricken.

Hard to imagine was the scene at 5.54pm on June 2, 1979, when the roads we saw shimmering in the midsummer heat danced to a different jig in the evening winter gloom.

Cadoux seems such an unlikely place for a powerful earthquake, but it was hit by a convulsion measuring 6.2 on the Richter scale. It opened 15km of great cracks in the ground, buckled roads, twisted railway lines, and cut power and telephone lines.

Left wrecked were the community hall, the Masonic hall, sports pavilion and the Post Office Store. WA’s second biggest earthquake (the biggest was a 7.3 at Meeberrie Station in 1941) moved the hamlet’s nine million litre water tank 43cm: unsurprisingly all the water leaked out.

Twenty-one of the 25 masonry buildings in Cadoux were damaged; only four of the 29 non-masonry were damaged. Falling masonry broke a child’s arm – the only recorded injury.

Most tall buildings swayed 200km away in Perth but little damage was recorded there, apart from the mercury leaking out of the Rottnest Island lighthouse.

After the ground stopped shaking damage to the school and houses was repaired, a new Post Office store built and an entirely sensible solution implemented for the lost recreation and social structures. All were gathered into the grand Cadoux Recreation Centre with social, sporting and cultural amenities – an astonishing air-conditioned complex for a tiny town of four houses, one occupied by the school principal.

Tennis, squash and basketball courts at the centre are used by the school and families living in the surrounding agricultural district.

For only $7 (pick up the key at the Post Office Store up the road), travellers can pull up motor homes or caravans for the night and use the kitchen and showers.

I also found a full bottle of Carlton Dry beer at the campground but alas, unlike the full can of Tooheys New I picked up on the Dundee Beach near Darwin, the free beer was a little spoiled by the sun. I shall continue to keep my eyes open on the free beer treasure hunt around Australia.

How utterly hospitable is Cadoux, little pinprick on the map selected for a wheat railway siding in 1929.

It was originally called Cado after the man who owned the farm where the bulk storage depot was built. A smart clerk did some checking and found the man’s name was actually Donald Cadoux, a French Canadian.

Pronounced a la francaise, Cadoux is phonetically Cado, which explained the anomaly when the name was written down. The council spelling was changed and the locals tweaked the sound to suit their sturdy English heritage. Instead of being pronounced Cado, Cadoux is now pronounced Cadoo.

Poor Donald never had to endure his name being tortured. He was killed at Gallipoli.

Apart from its fine recreation centre, peaceful stopover and hospitality, Cadoux has its Post Office Store, a rural supplies store, service station and its primary school for 25 pupils drawn from the surrounding area.

And despite the dried golden landscape, the Wongan-Ballidu shire where the town nestles has never been declared drought-stricken.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed