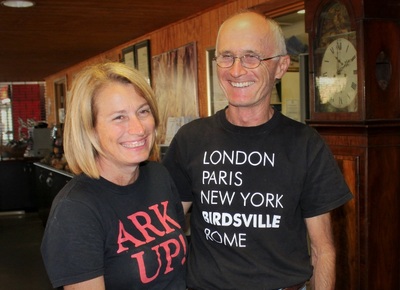

We limped into Arkaroola Wildlife Sanctuary in a 40-degree-plus swelter. Isabel was nursing a busted spring shackle and a blasted-out tyre. Shepherding us were Doug Sprigg and his partner Vicki. They and their two staffers, Roger and Gemma, could not have been more obliging as we sorted out spare part options that were to prove a little difficult.

We had intended ducking up to pay a quick visit to the village and then pushing on to the South Flinders but fate intervened and, as is often the case, made for a memorable experience.

Fortunately we became unshackled only a few kilometres from Arkaroola. A passing stranger called the village. Roger appeared. He and Tony jacked up Isabel and chained the spring to the chassis in a bit of bush mechanicking. Doug and Vicki turned up and followed as we crawled to what was to be our sanctuary for a week.

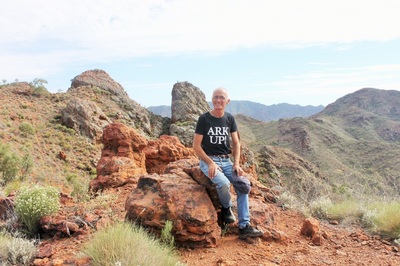

A pool, a bar, half the world’s population of pretty yellow-footed wallabies, friendly people, internet and no mobile service – what more could you want? Throw in curious tales of uranium mines, inspect glowing rocks, hear legendary stories about famous geologists, explorers and scientists who have explored Arkaroola, go for easy or tough walks along ancient gullies and hills or peer at the night sky through one of two observatories.

Then there’s the internationally famous Ridge Top Tour along a remarkable private 4WD track to Siller’s Lookout, a final scramble up a heart-stopping incline to gaze out on the spectacular ranges and the plains below.

Glittering through the hills was Lake Frome, the whitest salt lake in the Southern Hemisphere. So dazzling is the stark white that is used as a contrast material in analysing satellite data.

I don’t speak German but it was pretty easy to understand that Erica, Conrad and Lars from Switzerland, who were in the back of the open-top vehicle with me, were finding the ride uber-exciting. You can understand why the gate to the track is locked and why some people put it on their list of Ten Must-Dos in Australia.

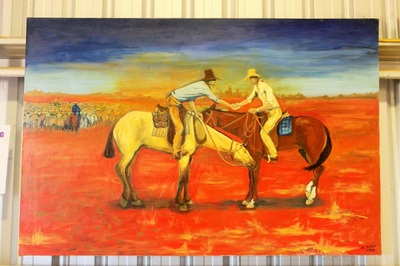

Arkaroola, 144,000 acres of the northern reach of the Flinders Ranges, is a unique venture into private conservation. The least attractive of pastoral lease offerings in the region, it was fenced off and taken up initially in return for the cost of eradicating feral animals.

Legendary outback geologist, conservationist, academic and author Reg Sprigg (whose achievements are staggering – google him) bought the lease in 1968 after failing to convince the South Australian Government to turn it into a national park. Reg took a month to confess his Arkaroola venture to his wife Giselda but over the next decades they created a unique retreat in the remarkable range of South Australia.

What started with a small motel has now grown to a complex with lodging for about 300 people, plus a caravan park and camp ground at the end of 130km of gravel road. That’s if you take the easy option from the sealed road running from Port Augusta to Leigh Creek. Lots more rough back routes are available from south and from the north …. think Innamincka, Cameron Corner, Birdsville.

“I don’t know much about the Flinders Ranges,” I confessed to Doug when we arrived. “What can you tell me about them?”

He swept me to a satellite map the size of a toilet wall and conjured up colliding and splitting continents, an ocean floor being hurled on high, massive pressures thrusting ancient strata into convulsions that formed the unique geographic surges of the Flinders Ranges.

In another corner he flicked on an ultraviolet light above a cabinet. Flinders rocks glowed green, orange, yellow and purple in startling radioactive luminosity.

Doug told story of how geologists fathomed that the uranium was being washed out of the ranges. On the east is Beverley mine, churning out yellowcake for Neal Blue’s General Atomics in the US; on the west is the huge Olympic Dam deposit of uranium, copper, gold and silver on Roxby Downs.

Arkaroola itself has had fairly mediocre mining success. When settlers in SA, our only non-penal colony, started heading for the Victorian gold rush the Adelaide chiefs feared for the settlement. They tried to persuade miners to stay home because there was gold in them thar Flinders. There wasn’t. Copper was found in enough quantity to get some digging but the ventures went broke.

Arkaroola is a geologists’ paradise and you learn you are walking in the footsteps of extraordinary people. Exploits of outback legend Reg Sprigg, of Santos and Moombi oil fields fame, are detailed in the book Rock Star by Kristin Weidenbach. (Reg found the oldest fossil in the world, drove the first vehicle across the Simpson with his wife and kids, did scary exploration on the ocean floor and was given the keys to the City of London for his services to geology.)

An Arkaroola peak is named after Reg’s close friend and confidante Sir Mark Oliphant, who searched here for uranium to make the world’s first atom bomb, worked on the Manhattan Project and then walked a humanitarian line, pleading for nuclear energy not to be used in weapons. A valley is named after Sir Douglas Mawson, Reg Sprigg’s mentor who also searched here for uranium.

Ridges of haughty grandeur tolerate what vegetation will endure the average rainfall of 170mm. Green deposits on rocks signal uranium but glittering shards tell of other fierce twists in the bowels of the earth.

New vegetation rose up after the floods of 1974, including a swathe of pines flanking the perilous Ridge Top road. Goats chewed off the saplings as their numbers exploded; more than 90,000 were shot over 20 years.

Keeping feral animals out of Arkaroola is still a battle but keeping the miners out was even tougher. When the SA government turned a little overly miner-friendly Doug led the fight to keep Arkaroola free from mining exploration.

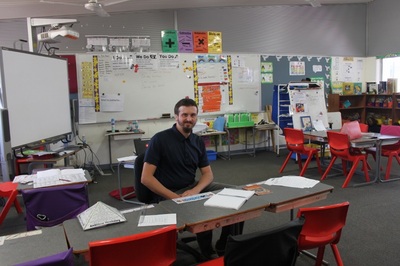

“Arkaroola really belongs to the people,” he said. “We run it like a national park, only we have to make a profit. We also make donations to conservation, research and education.”

His sister Marg was away when we were there. A geologist, she looks after the management side of Arkaroola while Doug flies tourists on flights over the ranges, drives them to the ridge tops and beyond and shows them the starry heavens on dark nights. Restless Sprigg energy is evident, laced with a passion for knowledge and spillway of stories.

At the helm in doors in Marg’s absence were Doug’s partner Vicki Wilson and vivacious cook and bar manager Gemma.

An arid range of strange and grim fascination, Arkaroola is a long way from an English country garden – or even the Sydney suburbs where Vicki lived until a year ago. She worked in finance projects for One Steel Arriom but escaped the harbour city as often as she could to go on bush camping trips.

Two years ago (“I was on a camping trip with my ex-mother-in-law,” she says wryly) she met Doug. She moved to Arkaroola and loves the vastly different life. ”I had to adapt to not being able to pop out to the shops for things but, apart from missing my family, I love this life.”

She pointed us at the waterholes and places of interest. We didn’t make it to the Paralana Springs site but that might be on the cards one day. A doctor thought the radon springs would be therapeutic for his patients. He set up a spa in 1923 and rattled one group of patients up there before it all became too hard because of the rugged remoteness and grim roads. It was shut down in 1924. No records show what happened to patients bathed in radon.

“There’s a really unusual bacteria in those springs,” said Vicki. “They tried to work out how it could survive and found it has a regenerative gene. It heals itself. They have only found that sort of thing in nuclear plant emissions.”

Wow. Of all the fascinating features in Arkaroola, that one grabbed me. A gene that repairs the body. Isolate that gene and you would think you would be sitting on something a lot richer than a mine chockful of uranium, gold and diamonds. Maybe we should get that spa going again.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed