Roads along the stock routes are usually broad and well-maintained to handle the road trains that have replaced the drovers since the 1960s.

Governments no longer maintain the bores that once watered mobs of 1000 to 1500 head a day. Bores were 20 miles apart and drovers were spread out to slot into them in turn.

If a mob was spooked and rushed (Americans call it a stampede), a following drover could leapfrog ahead on the stock route.

“The cattle were usually pretty quiet then though,” says Brian Thompson. “They were handled a lot more than they are today.”

Brian, 77, is one of a band of volunteers who man the Drovers Camp museum at Camooweal in the winter tourist season, talking about the old days and spinning a few yarns that raise eyebrows.

Most of the volunteers are former drovers. Brian just makes the ex-droving ranks – he was raised on a station and made one droving trip as an assistant horse tailer before his dad died and his family moved to Adelaide.

He ended up owning an optical manufacturing business but always yearned for the bush life, spending as much time as he could with his uncle Charlie Schultz on the Humbert River Station north-west of Top Springs.

Visitors to the Drovers Camp are shown maps of where the main stock routes went, what droving equipment was used and how the teams of riders, cooks and horse tailers integrated.

“Time was entirely different in those days,” said Brian, pointing out the patience and skills needed to make ropes and utensils, tend cattle on the move and make do in the bush. “These days people turn on a computer and if it’s not going in 10 seconds they’re blueing.”

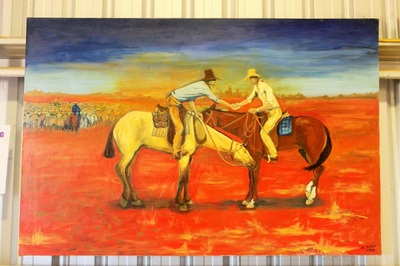

A man’s word is not so honoured these days either. Brian explains a giant painting inside the door of the shed, showing a drover and a cattle owner shaking hands on horseback. They have just done a headcount of the mob in the background, agreed on the tally and the pastoralist is handing the cattle over to the drover. Big money was tied up in those herds but a handshake was the only contract needed.

Dominating the interior of the shed is a mural by brilliant South Australian artist Yvonne Dorward, who took up painting when she was in her 40s. Ex-drover, ex-station manager and ex-buyer for cattle export, Jeff Hill, joins us and adds banter as Brian points out the cook setting the campfire, the tailer hobbling horses and the start of the first night watch.

Swags and saddles in front of the mural add dimension to the scene as Jeff, 77, spins a couple of yarns about droving days. We learn how important is was to have a good cook; how the horse tailer was up at 4am every morning to track 25 to 30 horses and get the hobbles off; and how singing to the cattle helped keep them quiet on night watch.

“You had to hear some of those blokes sing at night,” said Jeff. “They were bloody good.”

We learnt that if you had a good dog or a good horse for droving you had to keep a close eye on it. Drovers were not averse to swiping either when they mingled. Tony and I were also surprised to learn that Jeff had retired to Maryborough 10 years ago and lived only 10 km away from our home south of the city.

In the main gallery hang 55 portraits by Yvonne of legendary men and women who rode thousands of miles through the outback to take cattle to sales and rail heads.

Tribute is paid to the famed droving queen Edna Jessop. In 1950, aged 23, she became Australia’s first female boss drover, taking over from her father Harry Zigenbine. With her brother Harry and four ringers she pushed 1550 bullocks 2240km, from Halls Creek in Western Australia across the Barkly Tableland to the Dajarra railhead.

The eye-catching rider drove cattle across the Top End until the droving days came to an end 20 years later.

We wended our way down the old stock routes to Urandangie, one of the last pubs on the stock route before the drovers arrived at Dajarra. It’s hard to envisage Dajarra when it was the biggest cattle rail had in the world, marshalling more cattle each year than Abilene, Texas.

Little sign of its auspicious past remains. The rail line has long been torn up. A flapping hut might have been a railway platform. The pub has a lonely feel. Simon from Holland and Emily from Minnesota materialise in the service station: how would outback Australia open its doors if it could not employ wandering young foreigners who need to do three months work in the bush to get their visas extended to two years?

Across the road is a new set of yards for loading cattle on to road trains. The yards are substantial but barely noticeable on empty flat land stretching to the horizon. This is where Edna et al brought their cattle mobs to mill and bellow briefly before being shipped out by rail to travel east.

A thousand and more a day were herded up the ramps and on to the wagons. Those are the days the old drovers talk about when they fly to Camooweal on the fourth weekend of August.

They come from all over Australia to meet at the Drovers Camp, a kilometre east of the town. Like war veterans, their numbers are starting to dwindle every year but the history of the droving days will now endure.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed