Marsupial lions and carnivorous kangaroos roamed the luxuriant rain forest at Riversleigh but they had long gone when we arrived there.

In the intervening 20 million years the forest and pools had turned into rock with a smattering of grass. Barren it might look but Riversleigh, about 50 km south of Lawn Hill, is one of the most significant fossil sites in the world.

Curious people began scratching at white shapes in the rock on the cattle station just as the first federal politicians were getting together in the new city of Canberra. They started uncovering fossilised bones of more than 300 prehistoric species, some unknown to science before Riversleigh cattle station gave up its secrets. Scientists started work there in the 1960s. The fossil site has now been incorporated into the Lawn Hill National Park.

We had skipped Riversleigh when we had visited Lawn Hill 27 years ago because the road was pretty bad but I had always been intrigued by what is known as Site D.

Because of its grand reputation I had a naively romantic notion about what would be found at the great archaeological dig, envisaging a grand display of reconstituted bones or at least a dozen eccentric archaeologist types – possibly in pith helmets – digging in pits.

Nothing like that is on offer. A sign on the road says you have arrived at Site D and a path wanders off the dusty but not-too-bad road into an unprepossessing hill.

No one is in site but another sign warns you will be fined $3000, thrown in jail and your first-born not be allowed to nominate for the Australian Senate if you take even a wee rock from the site.

An information shelter harmonised into the landscape tells you what it is all about and then you wander around the rocks to see tiny bits of bone sticking out. The unusually hard limestone in the area preserved the bones of unique Australian prehistoric creatures, including a giant python with a girth about the size of a dinner plate.

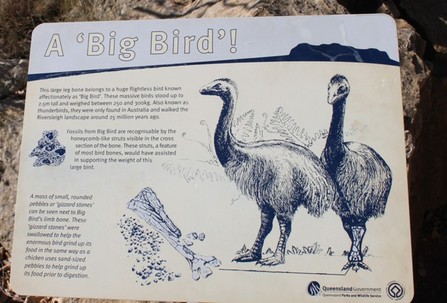

Big Bird is the star. You can admire a rather nice exposed fossil of his leg and the contents of his guts.

Big Bird is also known as a thunderbird. Remains of thunderbirds were found only in Australia. They stood about 2.5m tall and weighed between 250 and 300kg. Their leg bones were honeycombed to help support their weight.

The impressive leg bone poking out of the rock sits over a little cascade of pebbles, gizzard stones that helped Big Bird grind up the dirt and grit he absorbed as he pecked his way around the rainforest.

Apparently the archaeologists don’t work that particular site any more. They turn up in July each year and blow up another section, taking the large manageable chunks of rocks back to Mt Isa and Sydney. Lumps are dropped into acetic acid, which dissolves the limestone but not the fossils.

Fossils are outstanding in quality because the ancient spring-fed forest pools and lakes had a high concentration of calcium carbonate. The forest apparently formed a deceptive crust over the water, so the poor wildlife dropped through in big numbers to be quickly coated and buried in the hard limey mud. Chemicals in the ground water gradually altered the composition of the bones and teeth, turning them to stone.

Riversleigh’s marvellous menagerie disappeared when the climate cooled and dried out the rainforest about 10 million years ago

Sadly, no coal-fired power stations were around to keep the climate warm. I wouldn’t have minded seeing that thunderbird.

BELOW: Not eccentric archeaologists, just Barb and Phil wandering past a Big Bird bone site.

BELOW BELOW: Big Bird's leg bone and cascade of gizzard stones.

In the intervening 20 million years the forest and pools had turned into rock with a smattering of grass. Barren it might look but Riversleigh, about 50 km south of Lawn Hill, is one of the most significant fossil sites in the world.

Curious people began scratching at white shapes in the rock on the cattle station just as the first federal politicians were getting together in the new city of Canberra. They started uncovering fossilised bones of more than 300 prehistoric species, some unknown to science before Riversleigh cattle station gave up its secrets. Scientists started work there in the 1960s. The fossil site has now been incorporated into the Lawn Hill National Park.

We had skipped Riversleigh when we had visited Lawn Hill 27 years ago because the road was pretty bad but I had always been intrigued by what is known as Site D.

Because of its grand reputation I had a naively romantic notion about what would be found at the great archaeological dig, envisaging a grand display of reconstituted bones or at least a dozen eccentric archaeologist types – possibly in pith helmets – digging in pits.

Nothing like that is on offer. A sign on the road says you have arrived at Site D and a path wanders off the dusty but not-too-bad road into an unprepossessing hill.

No one is in site but another sign warns you will be fined $3000, thrown in jail and your first-born not be allowed to nominate for the Australian Senate if you take even a wee rock from the site.

An information shelter harmonised into the landscape tells you what it is all about and then you wander around the rocks to see tiny bits of bone sticking out. The unusually hard limestone in the area preserved the bones of unique Australian prehistoric creatures, including a giant python with a girth about the size of a dinner plate.

Big Bird is the star. You can admire a rather nice exposed fossil of his leg and the contents of his guts.

Big Bird is also known as a thunderbird. Remains of thunderbirds were found only in Australia. They stood about 2.5m tall and weighed between 250 and 300kg. Their leg bones were honeycombed to help support their weight.

The impressive leg bone poking out of the rock sits over a little cascade of pebbles, gizzard stones that helped Big Bird grind up the dirt and grit he absorbed as he pecked his way around the rainforest.

Apparently the archaeologists don’t work that particular site any more. They turn up in July each year and blow up another section, taking the large manageable chunks of rocks back to Mt Isa and Sydney. Lumps are dropped into acetic acid, which dissolves the limestone but not the fossils.

Fossils are outstanding in quality because the ancient spring-fed forest pools and lakes had a high concentration of calcium carbonate. The forest apparently formed a deceptive crust over the water, so the poor wildlife dropped through in big numbers to be quickly coated and buried in the hard limey mud. Chemicals in the ground water gradually altered the composition of the bones and teeth, turning them to stone.

Riversleigh’s marvellous menagerie disappeared when the climate cooled and dried out the rainforest about 10 million years ago

Sadly, no coal-fired power stations were around to keep the climate warm. I wouldn’t have minded seeing that thunderbird.

BELOW: Not eccentric archeaologists, just Barb and Phil wandering past a Big Bird bone site.

BELOW BELOW: Big Bird's leg bone and cascade of gizzard stones.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed