No houses can be rented for less than $3500 in Onslow. Food and fuel are both expensive and the 800 permanent residents are either reeling or rejoicing as the giant Wheatstone gas plant mushrooms a few kilometres down the coast.

About 5000 workers are beavering away on the construction site, a 45-minute drive away. Wheatstone employees are not allowed into the town except on special occasions; those housed at the Discovery caravan park are bussed to and from the work site.

Prices at the second caravan park are fairly steep if you can get a site – many permanents are mine workers too.

Onslow is an intriguing town caught in a transition that shows the dichotomy of wealth and hardship created by the resources boom of northern Australia. We had skipped the town on previous trips to WA and no one recommended it since but we decided to poke the 80km into the town best known for its battering from cyclones.

It has a salt mine with 500 to 600 workers and an early history of pearling and gold along with its old port, the main reason for the town evolving in the early 1980s. The town moved from the early site after the Ashburton River silted up and now sits on the coast near Beadon Point.

It has a superb war memorial park facing out to sea (see seat sculpture above) , beaches and fishing spots near the town, half a kilometre of free camping along the Ashburton, a public water point in town and a terrific visitors centre and museum.

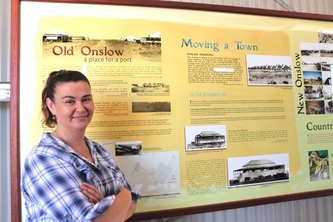

Carol Stratford, the vivacious manager of the visitors centre, is an enthusiastic promoter of her town. The museum’s prize exhibit is the train that used to run from the jetty to the town but the cyclone stories are absorbing.

Onslow is Australia’s most cyclone-prone town. It has had a biennial average of cyclones with winds of more than 95kmh. Cyclone Trixie in 1975 smashed the aenometer at 246km.

In 1961 three cyclones hit in six weeks, one dropping the barometric pressure to 27.3 inches – an Australasian record. The town sort of shuts down for tourists in the summer cyclone season because the shelters don’t have enough room for caravanners and the sites don’t have tie-downs as in Karratha. The contractors have to leave when the town goes on yellow alert.

Large murals have been put up beside the quaint little train to tell Onslow’s chequered story at the museum (which also closes for summer). It was a submarine supply base and was the southern-most Australian city bombed by the Japanese in WW11. In the 1950s it was a base for the British atomic tests at Montebello Islands.

It’s well worth the drive in to contemplate the town and its story, told in the museum and in conversations with the locals.

Carol is cautious about the effects Wheatstone is having on the town but points to some amenities that have been provided by the gas industry. Her visitor numbers are down to 25%, however, because tourists have been frightened away by prices and scarcity of caravan sites.

That is a shame. Onslow’s history is absorbing and its current economic dilemmas are thought-provoking.

No one is quite sure what the long-term effects of Wheatstone will be on Onslow. The second largest gas development in Australia (Inpex in Darwin will be bigger) is expected to have thousands on-site in construction and development for the next 15 to 20 years but after that only a few hundred will remain as operational crew.

Wheatstone employment for local workers and contractors is petering out. Apart from Discovery, the rest of the workers are FIFO and rarely seen.

Apparently Chevron originally wanted to build the Wheatstone plant right in Onslow but locals were alarmed at what would happen to their town. Chevron changed plans and built a little down the coast to process the off-shore gas. Now they are talking about a supermarket, bowling alley and other facilities being built at the Wheatstone site.

What that will all mean in 20 years is difficult to assess but lessons to be learned lie in Onslow.

About 5000 workers are beavering away on the construction site, a 45-minute drive away. Wheatstone employees are not allowed into the town except on special occasions; those housed at the Discovery caravan park are bussed to and from the work site.

Prices at the second caravan park are fairly steep if you can get a site – many permanents are mine workers too.

Onslow is an intriguing town caught in a transition that shows the dichotomy of wealth and hardship created by the resources boom of northern Australia. We had skipped the town on previous trips to WA and no one recommended it since but we decided to poke the 80km into the town best known for its battering from cyclones.

It has a salt mine with 500 to 600 workers and an early history of pearling and gold along with its old port, the main reason for the town evolving in the early 1980s. The town moved from the early site after the Ashburton River silted up and now sits on the coast near Beadon Point.

It has a superb war memorial park facing out to sea (see seat sculpture above) , beaches and fishing spots near the town, half a kilometre of free camping along the Ashburton, a public water point in town and a terrific visitors centre and museum.

Carol Stratford, the vivacious manager of the visitors centre, is an enthusiastic promoter of her town. The museum’s prize exhibit is the train that used to run from the jetty to the town but the cyclone stories are absorbing.

Onslow is Australia’s most cyclone-prone town. It has had a biennial average of cyclones with winds of more than 95kmh. Cyclone Trixie in 1975 smashed the aenometer at 246km.

In 1961 three cyclones hit in six weeks, one dropping the barometric pressure to 27.3 inches – an Australasian record. The town sort of shuts down for tourists in the summer cyclone season because the shelters don’t have enough room for caravanners and the sites don’t have tie-downs as in Karratha. The contractors have to leave when the town goes on yellow alert.

Large murals have been put up beside the quaint little train to tell Onslow’s chequered story at the museum (which also closes for summer). It was a submarine supply base and was the southern-most Australian city bombed by the Japanese in WW11. In the 1950s it was a base for the British atomic tests at Montebello Islands.

It’s well worth the drive in to contemplate the town and its story, told in the museum and in conversations with the locals.

Carol is cautious about the effects Wheatstone is having on the town but points to some amenities that have been provided by the gas industry. Her visitor numbers are down to 25%, however, because tourists have been frightened away by prices and scarcity of caravan sites.

That is a shame. Onslow’s history is absorbing and its current economic dilemmas are thought-provoking.

No one is quite sure what the long-term effects of Wheatstone will be on Onslow. The second largest gas development in Australia (Inpex in Darwin will be bigger) is expected to have thousands on-site in construction and development for the next 15 to 20 years but after that only a few hundred will remain as operational crew.

Wheatstone employment for local workers and contractors is petering out. Apart from Discovery, the rest of the workers are FIFO and rarely seen.

Apparently Chevron originally wanted to build the Wheatstone plant right in Onslow but locals were alarmed at what would happen to their town. Chevron changed plans and built a little down the coast to process the off-shore gas. Now they are talking about a supermarket, bowling alley and other facilities being built at the Wheatstone site.

What that will all mean in 20 years is difficult to assess but lessons to be learned lie in Onslow.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed